Yesterday was Groundhog Day, so naturally I rewatched the 1993 masterpiece Groundhog Day—because that’s what you do when you’re part of this particular cult of cinephiles. And yes, I do mean cult. Turns out I’m not alone in this ritual. Every February 2nd, devotees across the globe fire up their streaming services, dust off their DVDs, or—let’s be honest—illegally stream the thing, settling in for 1 hour and 43 minutes of what might just be the finest comedic performances ever committed to celluloid.

Speaking of time, this cinematic gem is genuinely, unironically timeless. We’re talking not just one of the greatest films ever made, but also somehow one of the best films of 1993—a year that gave us Schindler’s List, Jurassic Park, The Fugitive, True Romance, Tombstone, and Philadelphia. Yeah. THAT kind of company.

But here’s what elevates Groundhog Day beyond “just” being a brilliant comedy packed with brilliant performances: Harold Ramis. The man helmed this beast while co-writing the script with Danny Rubin, bringing his legendary loose, hyper-collaborative directing style to every frame. Ramis had this beautiful philosophy of accepting ideas from anyone on set—grips, extras, the craft services guy—making everyone feel like co-creators. When people feel ownership over a project, they bring their A-game. And boy, did this gamble pay off. The film was successful. Is successful. Will always BE successful.

The internet is drowning in Groundhog Day think pieces (and here I am, adding to the flood). But today, I’m stripping things down to the essentials: the premise, the structure, and—most crucially—what makes this film such a profound, soul-stirring experience that demands repeated viewings.

Fair warning: SPOILERS AHEAD. Massive ones. If you somehow haven’t seen this film, stop reading immediately, go watch it, then come back. Seriously. I’ll wait. And when you return, drop a comment with your thoughts! I’m dying to hear how this movie hit you, what it made you feel, how many times you’ve watched it while crying into your cereal.

So let’s talk community. Because that’s what sits at the heart of this film—a tight-knit town with an annual ceremony that brings everyone together in collective, small-town joy. Enter our “hero”: Phil Connors, a snobby, big-city TV weatherman dispatched to cover said ceremony, treating the whole affair with maximum condescension. Poor Phil. His ego writes a check his soul can’t cash, because he gets trapped—inexplicably, mysteriously, beautifully—in a time loop, doomed to relive Groundhog Day over and over and over again.

The character arc:

Imagine the devil becoming an angel. Imagine Agent Smith becoming Neo. Imagine an ICE officer becoming the Buddha. Just to give you an idea of the impossible task the writers worked to create in the character arc of Phil. And the playground where all this takes place? Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, a tiny mid-Atlantic town filled with the most lovable and quirky people in the world.

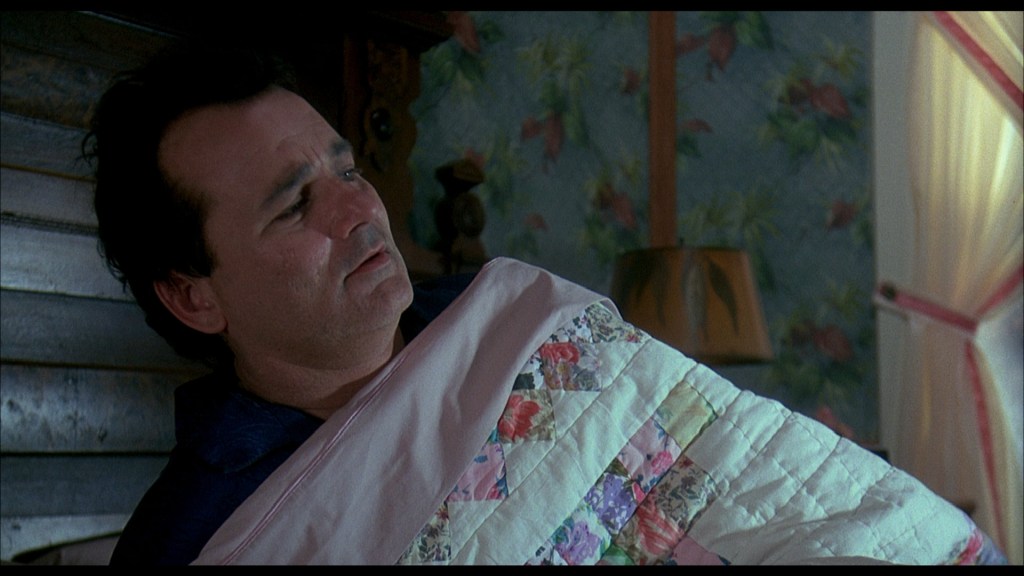

The supporting cast? Perfection. Every peripheral character pops. Take that very first scene in the bed and breakfast when Phil stumbles downstairs for coffee. The sweet proprietor (the wonderful Angela Paton) tries making small talk, and we watch Phil radiate pure irritation at this innocent, kind woman. The contrast is chef’s kiss—immediately establishing just how far this miserable bastard needs to travel before we’ll root for him the way we instantly root for her.

Day three: Phil has an epiphany. This is it. This is his life now. Stuck in what he considers the worst possible day in the worst possible place at the worst possible time. So he does what any self-respecting narcissist would do: he rebels. “I’m not playing by their rules anymore,” he declares to the universe, proceeding to commit crimes with glee: smashing mailboxes with his car, leading cops on a chase, landing in jail.

He’s severed himself from society completely. From laws, from norms, from basic human decency. What he hasn’t figured out yet is that this path leads straight to soul-crushing loneliness. Because what are we, really, without community? Without connection? Without shared agreements about right and wrong, truth and falsehood, acceptable and unacceptable?

Next morning: he wakes up in his B&B room (post-jail), and realizes something intoxicating—he’s FREE. Free from consequences. Free from rules. Free from society’s chains. But here’s the cruel joke: he’s NOT free from himself. And that self? That’s the source of all his misery. It’s also, paradoxically, the key to his eventual awakening, his return to wholeness, to community, and to love.

What follows is a montage of gluttony: booze, cigarettes, mountains of sweets and fried garbage, meaningless sex, a deep dive into hedonism that reveals pleasure-seeking’s empty core.

One of the film’s greatest strengths? It never explains the time loop. Not once. No cosmic justification, no mystical origin story, no hand-waving sci-fi technobabble. It just is. And we accept it. We accept that this egomaniac has been imprisoned in a metaphysical mirror designed to force self-confrontation at a level most humans never experience.

Yet Phil wants what we ALL want—genuine, soul-deep love. He’s desperately in love with Rita, his producer. But he can’t win her over. Not as he currently exists. Despite his increasingly elaborate schemes (all dishonest), they never work. Their union remains impossible until he undergoes genuine transformation.

Rita is authenticity personified, played by the genuinely lovely Andie MacDowell. She’s everything Phil isn’t—sincere, open, real. The audience KNOWS these two don’t belong together. Phil knows it too. He just doesn’t care. He treats her like a conquest, weaponizing his temporal imprisonment to learn her preferences, her romantic ideals, crafting an elaborate disguise that makes him appear to be everything she desires.

Normally we’d dismiss this creep as exactly that—a creep. But Phil is played by the charming Bill Murray. This man could play Hitler and we’d still find ourselves rooting for him. That’s the dark magic of a truly gifted comic actor: anti-heroes become heroes, and we follow them anywhere, smiling the whole way.

What Groundhog Day actually IS—beneath the laughs, beneath the high concept—is a story about a shallow, surface-dwelling man diving into the depths. Into despair. Into death. Into finality. Into ultimate powerlessness. And emerging transformed: selfless, giving, caring, talented, humble, and capable of the deepest possible love.

How many films feature THIS kind of character arc? An arc that whispers to everyone who struggles with self-loathing: You are redeemable. No matter your worst actions, your ugliest traits, your deepest shame—transformation is possible. This is why Groundhog Day might be the most hopeful film ever made.

Phil finally admits to Rita: “I don’t like myself.” Boom. There it is. The audience has been waiting for this revelation—confirmation that Phil shares our assessment of him. But he still hasn’t figured out how to escape the prison of being trapped with someone he despises and cannot flee.

He wanders past ice sculptures—witnessing beauty, skill, commitment. Everything he lacks as a shallow hack. He wakes depressed. The depression doesn’t lift. He kills himself. Again. And again. And again. Nothing works.

Here’s what’s beautiful about Phil’s transformation: every other character remains exactly the same. Phil’s real awakening isn’t about them changing—it’s about recognizing the perfection that’s been there all along.

After his final suicide, when Rita identifies his corpse, everything shifts. Death becomes the catalyst—literal, visual, undeniable.

From this moment forward, Phil never lies again. He comes clean to Rita, genuinely accepting his fate—this day, forever. His honesty is real. They spend their first day in genuine connection. No manipulation. No sexual agenda. Just two people, honestly present with each other. It’s heartwarming.

Love changes Phil. That genuine connection with Rita cracks him open. Suddenly he’s charitable—giving money to the homeless man, bringing pastries and coffee to his crew, actually listening to other people’s ideas. He starts piano lessons, not because Rita mentioned liking musicians, but because he hears piano music in a café and feels moved.

But when the homeless man dies—despite Phil’s efforts to feed him, warm him, save him—Phil can’t accept his powerlessness. He launches a crusade to prevent this death, trying everything, day after day. Still, the man dies.

And here, Phil learns the hardest lesson: death is unavoidable. It’s coming for all of us. And paradoxically, death is what makes life precious. Without death, we’d never understand how valuable each moment is, how irreplaceable our loved ones are. Death is a teacher. Death is a gift.

Then comes his masterpiece: the final iteration of his seemingly endless Groundhog Day. He spends it serving everyone—saving a boy’s life, changing tires for elderly women, performing the Heimlich maneuver to save the life of a townsperson, preventing a couple from calling off their wedding. He earns the right to live. And when he wakes on February 3rd, Rita is beside him, and the future stretches out before them both.

Remember: the union of opposites, of lovers, created all of us. Life itself springs from love. So the film argues—and I believe it—that love IS the goal. The whole point.

Why does this story work?

We learn nothing about Phil’s backstory. No family drama, no childhood trauma, no origin story. Nothing. It’s all implicit in how he behaves NOW. And this absence is crucial—it makes the story universal.

Because we’re ALL egocentric. We ALL started out self-centered. We ALL dismiss others while obsessing over our own desires and comfort.

If we knew Phil’s whole psychological history, the film would lose its power. We’d see him as a specific case study rather than a mirror reflecting our own shallow, judgmental, growth-starved selves.

Finally, here’s the essence: Groundhog Day is a story about escaping selfishness. A transcendental journey from “I” to “We.”

Which is why, in the end, Phil could finally, truthfully say to Rita:

“I got you, babe.”

Leave a comment